Experts who developed the guideline found that poor transition could be damaging to vulnerable patients. They may become dependent on the hospital’s care or struggle to keep in touch with family and friends once they are back home.

In addition to the personal cost for patients, poor transition is costly for the NHS if people remain in hospital due to to delayed discharges.

Professor Gillian Leng, deputy chief executive at NICE, said: “If a transition goes wrong, it can have a devastating impact on people who already have a fragile state of mind. For people with mental health problems the risk of suicide or self-harm is particularly high in the days before and after hospital stays.

"We need mental health practitioners to communicate well with people during their care, and treat them in an empathetic manner. Hospital and community mental health teams must also work closely together to deliver structured, consistent care. This guideline sets out how to achieve that.”

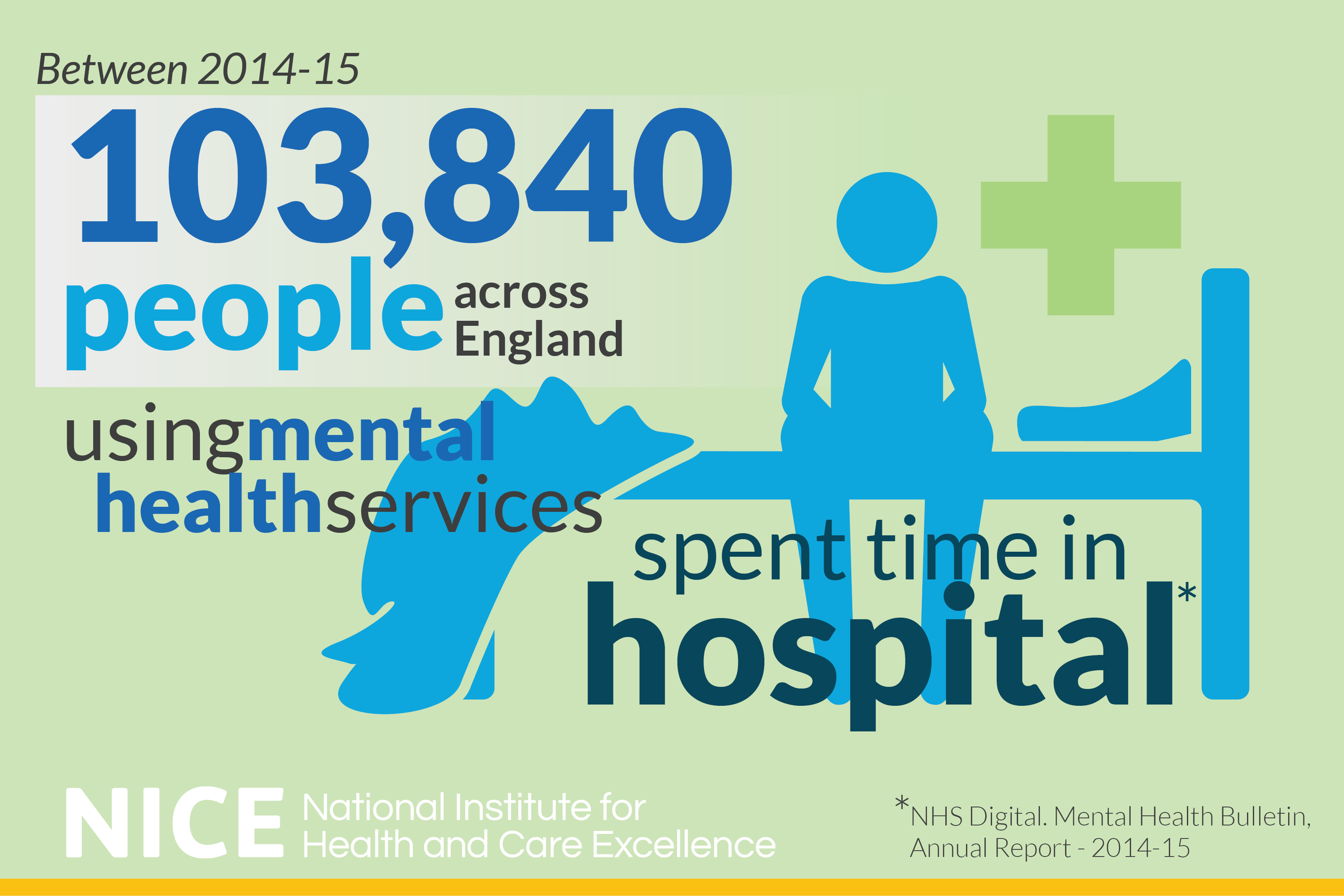

1.8 million people used NHS mental health services in England last year. More than 100,000 of them spent some time in hospital.

Between 2003 and 2013, almost 1 in 5 people using mental health inpatient services died by suicide within three months of being discharged.

The guideline highlights that this risk is particularly high in people who have to be admitted to a hospital away from where they normally live. It says there should be a named practitioner assigned from the person’s home area who will work closely with their hospital team. They should be involved in regularly reviewing care plans and can help assess a person’s suicide risk before discharge and set out how to best support them.

The guideline says people with mental health problems should be involved in decisions when they are going into and out of hospital.

Mental health staff working in hospitals should start working to build relationships with people as early as possible. For instance, people should be given the chance to visit and familiarise themselves with hospital units where possible before they are admitted. Equally staff in community mental health services should get involved early on to help prepare people for discharge.

It also says that people should be offered tailored education sessions in the lead up to and after their discharge. These sessions should involve their family and carers and should focus on how to help them cope with their triggers and symptoms.

Rebecca Harrington, an independent social care and health consultant and chair of the group that developed the guideline said: “Being admitted to hospital does not have to be a negative experience for people with mental health problems.

"There is good evidence to show that building therapeutic relationships early on may help prevent people feeling coerced. This means they benefit more from their treatment in hospital. This new guideline sets out how people can be well supported before, during and after their time in hospital, so they avoid being isolated and stigmatised.”

The guideline aims to help everyone needing mental health support to have a positive transition between services.

UPDATE - In March 2017, the charity Mind reported that at least one in 10 mental health patients are not getting any follow-up in the first week after leaving hospital. NICE is reviewing these findings to see if any further changes need to be made to better support people using mental health services.