Smoking is a risky, costly behaviour. Cessation as ‘treatment’ can lead to lower drug doses, fewer complications and hospital re-admissions, higher survival rates, better wound healing and decreased infections. Persuading smokers to abstain is challenging. Annually, nearly half a million smokers are admitted to secondary care. AMUs are high patient turnover areas, presenting an ideal opportunity to offer smoking support and to apply and try to adhere to guidance.

NICE PH48 guidance is specific to acute, mental health and maternity services – these patient groups (and COPD) present to AMU.

NICE NG15 COPD guidance re-iterates that fundamentals of COPD care should be revisited and actioned before escalation of treatment (smoking cessation is a key part of that).

NICE Quality Standard for COPD (QS10) includes a pertinent quality statement, that ‘people with COPD who smoke are regularly encouraged to stop and are offered the full range of evidence‑based smoking cessation support’.

Example

Aims and objectives

Our aim was to bring about change in current practice for smoking cessation to improve patient care and experience by engaging and upskilling the multidisciplinary team (MDT).

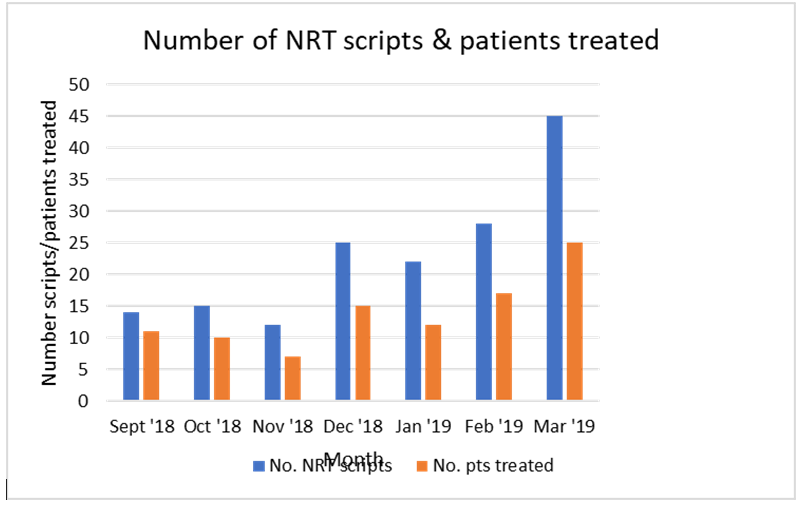

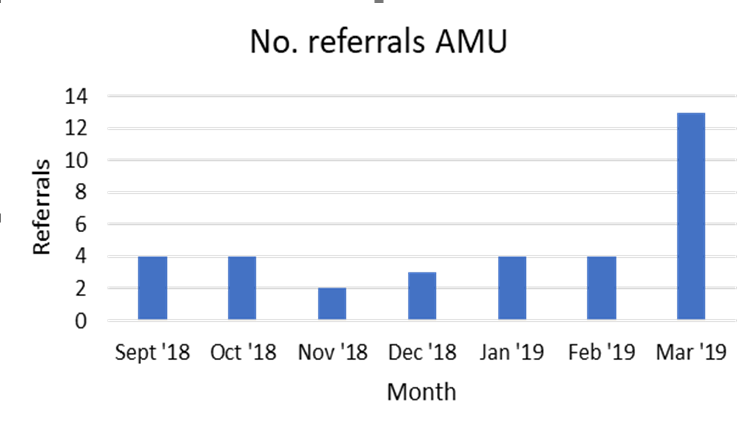

Our objective: To achieve a 25% increase in the number of cessation referrals and nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) prescriptions within 3 months.

Our aim intended to make positive change and to make each healthcare contact ‘count’ for patients, some of whom may be more vulnerable. This is important for their future morbidity and mortality but also for those around them due to impact of passive smoke or the effect on foetal health. This was also important as the interventions are relatively low cost, accessible, evidence based and endorsed by NICE, hence as part of quality care should be offered to patients.

Our intention was to train staff to make them more knowledgeable and to debunk any common myths around smoking cessation and the associated medication (for example: ‘I can stop cold turkey’). Hence, staff would be more likely to discuss and offer treatment to patients but also to consider cessation for themselves if applicable. Some of the staff in AMU are rotational or transient, hence learning was intended to be transferrable to any other area of practice that any staff moved to. The essence of the project was to raise awareness, apply the guidance and use the quality standard to understand and address any barriers to this (if identified) to try to benefit as many patients as possible.

Reasons for implementing your project

Limited smoking support in place for inpatients on AMU:

Baseline 2018 data showed low rates of NRT prescribing and follow up referrals suggesting sub-optimal patient care was being provided and our smoking CQUIN targets were also not being met. The smoking cessation programme manager was in post across two hospitals (hence spread thinly) and root cause analysis revealed that the ’lone professional’ approach was not effective in bringing about continual change. Although NRT was available as stock on the ward, there was a need for a prescription before administering (reliant on doctors prescribing NRT).

We felt that there was an opportunity to improve the quality of patient care and productivity of team input within AMU to increase prescribing of NRT, appreciating that this would increase drug costs. Our 56 bedded AMU (within a 500-bed acute London hospital) has a fast turnover of patients of mixed backgrounds and a range of medical/mental health problems; staff other than doctors can support smoking cessation treatment.

We took feedback and views from staff on the current smoking cessation management practice before starting the project and used the following quality improvement tools: driver diagram, process map and stakeholder map to identify potential improvements and key stakeholders.

Proposals included joint pharmacy/smoking advisor working, further stakeholder engagement, identification of smoking champions, increased training (doctors/pharmacists to increase awareness, referrals and prescribing) and further health promotion with other AMU disciplines.

How did you implement the project

A quality improvement approach was adopted to develop a more collective cessation model. A structured Plan-Do-Study-Act cycle was made to test interventions.

Change Idea: MDT approach -‘everyone is responsible’. From January-March 2019, the following interventions were tested:

- Establish champions promoting cessation (Jan)

- Launch newly developed visual prescribing guide (Feb)

- Monthly training (Prescribing and ‘Very Brief Advice’)

- Project review

How changes were planned and tested

- Bi-monthly project assessment (pharmacist and smoking programme manager)

- Looking at output from referrals and NRT for each cycle

- Reviewed challenges in each cycle i.e. unanticipated, it became apparent certain cohorts (e.g. unsafe swallow) may require tailored treatment/specialist input which we sought where necessary.

- Challenges with mental health patients e.g. dementia and consent – individual best interest approach

- The project was undertaken pre-implementation of trust-wide electronic health records (presenting challenges for future data extraction). Plan to work with EHRS systems to improve on challenges presented since EPIC go live

Measuring Success:

- Electronic in-patient prescriptions, smoking referrals and feedback forms (pre/post training evaluation forms from pharmacy staff/doctors) were collated and reviewed (Excel and via LifeQI platform) to monitor progress.

- There weren’t any specific costs to run the project per se but time/staff resource for training was a cost pressure and the training was delivered within existing roles (Pharmacist and smoking manager)

Key findings

By March 2019, the new model resulted in a 325% uplift in smoking referrals. The number of prescriptions created and patients prescribed NRT increased by 205% and 208% respectively (marked improvement from 2018 data). There was naturally a slight increase in drug cost due to increased prescribing, as expected. Short term we weren’t able to relate the positive changes to numbers of ‘quit attempts’ for patients and this data was not available to us within the hospital.

Post-training survey feedback reflections from staff included:

“Increased awareness on the subject”

“I feel confident to prescribe NRT appropriately now”

“I feel more able to counsel on NRT use”

“Very useful training”

“I will actively make referrals now”

Cessation prescribing and referral rates increased (acknowledging quality not assessed, or which single intervention caused this). These contributed to patient wellbeing and achieving CQUIN targets. Doctors and pharmacy staff reported increased empowerment to discuss cessation during consultation, initiate NRT and make onward referrals (which may have increased cessation rates).

Conclusion: We exceeded our objective and our project follows national guidance, encouraging patients to quit smoking, demonstrating a model that is effective in acute care.

A multidisciplinary, quality improvement approach is key to enable patients to quit smoking. Through smoking champions, frequent training and more collaborative working, staff can support patients to be healthier.

Key learning points

A MDT team approach is very effective (TEAM together everyone achieves more) but sustaining change is hard and requires investment.

We demonstrated the value of combined input/ownership, translating to better patient care. It became apparent that certain patient cohorts may require tailored treatment/specialist input which may delay receiving appropriate NRT. At the planning stage we hadn’t considered specific patient groups unable to use recommended pharmacotherapy or require a different therapeutic approach e.g. patients with swallowing difficulties or those with head/neck cancers (unable to use products in the oral cavity). Such patients aren’t the usual AMU cohort but it prompted treatment strategy review.

The project was undertaken pre-implementation of organisation wide electronic health record (presenting challenges for modifying approach/future improvement) and impacted project continuity. We were unaware of the launch date for this when initially reviewing baseline data and making changes, however, we were able to capture reliable data up until the health record change.

The impact of (and planning for) organisational factors that may have special cause variation is vital for future projects or repeating. Training feedback generated suggestions for this (e.g. prescribing support/order sets) informing more focused delivery.

Our training targeted doctors and pharmacy staff initially as they are more able to write/influence prescriptions. Nursing staff could’ve been included in our initial training but staff/time constraints limited this as there was no resource to provide the training and was logistically difficult to achieve with nursing rotas.

Planning from the outset, identifying and engaging the correct stakeholders is key. It is also useful to gauge/understand what/who the obstacles may be in order to try to address and overcome them or consider a contingency for maximal success. Positivity and consistency are important to keep engagement and momentum.