This project describes the development and implementation of a service improvement concerning the referral of patients with breast symptoms (including those suspicious of breast cancer) from primary to secondary care.

The project had the following focus:

1). To optimise the urgent (where cancer is suspected) referral process with no reduction in cancer diagnosis rates seen.

2). To support primary care in the enhanced management of patients with low index of suspicion (where cancer is not suspected) symptoms with cancers diagnosed in these patients remaining below screening rate (approximately 1%) and unchanged compared with 2019 and,

3). To facilitate the breast symptom Rapid Diagnostic Centre pathway and its associated outcomes.

The project has relevance to the suspected cancer recognition and referral process outlined in NG12. It is also relevant to other NICE resources including Patient experience in adult NHS services overview, Patient Experience in Adult NHS Services CG138, and NICE Implementing Guidelines in the NHS (PDF).

Example

Aims and objectives

Aim

- To enhance the management, referral, assessment, and experience for patients with breast symptoms who:

- Require urgent cancer referral to secondary care (NG12: 1.4.1) and

- Require initial primary care support for low index of suspicion symptoms (NG12: 1.14.8; NG12: 1.4.3); through the application of a validated local proforma (NG12: 1.16.7, Patient experience in adult NHS services overview; CG138, NICE Implementing Guidelines in the NHS).

It is further anticipated that achieving this aim will enhance patient outcomes in association with mortality, 1- and 5-year survival, stage at diagnosis and quality of life (NICE QS12).

Objectives:

Primary Objective:

- To determine the utility of an adapted local breast symptom referral proforma (NG12: 16.7) by quantifying outcomes to secondary objectives below:

Secondary Objectives:

- To compare and contrast urgent and non-urgent primary care referrals post implementation of service change (NG12: 1.4)

- To compare and contrast breast pain referrals post implementation of service change (NICE Scenario – breast pain)

- To compare and contrast cancers diagnosed post implementation of service change (NG12: Introduction

- To compare and contrast primary to secondary care referral patterns and impact on unwarranted variation post implementation of service change (NICE Charter:10)

Reasons for implementing your project

Background

The breast assessment service in our large South of England acute NHS Trust currently offers cancer services to a population of approximately 1,000,000 people in our region and the surrounding areas.

In 2018 our service was functioning under considerable strain due to the collective impact of staff shortages (particularly mammographers and radiologists), compromised ability to provide a ‘single visit’ service consistent with NICE Guidance 1, 2, supporting optimal patient experience 3, and maintain an acceptable performance against national standards CSV file 12.

Rationale for Change

An audit within our Trust reviewing patients with breast symptoms assessed 2013-2018 observed a large volume of referrals for breast pain and observed that these referrals conveyed to low cancer conversion rates (Lekanidi, currently unpublished, and a further local audit Tse and Preston 2019).

Additionally, work published with the Association of Breast Surgery (ABS) Year Book 2019 by Nottingham Breast Institute, demonstrated a service improvement outlining redesign of their primary care referral form and signposting enhanced primary care support for patients with breast pain, eczema and gynaecomastia (benign increase in size of male breast tissue). Nottingham Breast Institute reported this service change resulted in a significant and sustained reduction in low index of suspicion breast symptom referrals and no significant impact on cancer diagnosis rates (Sawers.L, 2018: 92-94).

In October 2019, our Brighton and Sussex University Hospitals NHS Trust service lead, Mr Charles Zammit, requested we consider developing a model inspired by the work of Nottingham Breast Institute, for our service and that this was aligned with NICE guidance.

How did you implement the project

Project Implementation

We completed NICE NG12 baseline assessment tool and NICE Implementing Guidelines in the NHS (PDF) tools to better understand the need for improvement in our service. Findings from the NG12 baseline assessment tool included considerable variation in type and quality of referral documentation received and a potential need for enhanced support/collaboration between secondary care and referring primary care colleagues, particularly in relation to non-urgent referrals (attachment 1).

We then completed a project proposal and presented this to our cancer service managers. The proposal recommended one day per week senior nurse clinical oversight for a period of 20 weeks. Our service managers were supportive of the proposal however there were no service funds available to facilitate this, at the time.

We then made an application for funding to Surrey and Sussex Cancer Alliance (SSCA) who supported the project. Surrey and Sussex Cancer Alliance also contributed significant expertise and internal knowledge through assistance including stakeholder introductions, project management expertise and regional group collaboration; all of which were significantly impactful in terms of project success.

The project was subdivided into 4 phases (Table 1) below. At the time of writing the project is now entering phase 4

Project challenges and how these were overcome

This service change impacted on multiple stakeholders from different settings (including patients, primary and secondary care service leads/managers, Cancer Alliance colleagues/partners, commissioning leads, clinicians and administrative teams).

The project impacted upon the referral process for over one hundred busy primary care practices in East and West Sussex and we anticipated (and received) concerns and questions from stakeholders, particularly primary care GPs.

Challenges raised included:

- Clinical concerns (will cancers be missed? Will patients receive sufficient care/support?)

- Pathway concerns (will this service change result in unintended consequences affecting resource provision and service delivery?)

- Process concerns (how will the referral pathway be supported, and will referrals be robustly delivered/received?)

- Governance concerns (is this service change NICE compliant? How will cancer waiting times be influenced?)

Without exception, all concerns raised positively shaped the delivery of the project however, there were occasions when any one of these challenges could also have permanently arrested it and resulted in project failure. A strong mitigating factor guarding against this latter risk was shown to be the support of key senior stakeholders (service lead, admin lead, finance lead, regional cancer alliance lead, primary care and clinical commissioning group leads) which we had collaborated extensively with to secure, in the early part of the project.

When initially outlining the requirements for this project, the key elements identified were historical evidence, understanding NICE guidance, service capacity/demand understanding, prospective data collection, collaboration with stakeholders, a key admin team project link and finally my role offering clinical oversight and project management. On reflection, this was a rather simplistic view on my part and it quickly became clear to me that this approach should be reframed if the project was to be a success. I needed to let go of the idea this project was for me to lead and embrace the concept of ‘co-production’ where the focus is one of sharing ideas, care delivery and – most importantly – ownership of the project and its outcomes.

Having realised this, my starting point changed from a linear project vision to a more fluid approach throughout and collaboration with all stakeholders during the life of the project, became a central priority. This liberated beneficial outcomes I had not previously envisioned or considered. These included an enhanced understanding and relationship between our services and teams, and specific benefits such as improved patient triage in secondary care, increased safety and speed of appointment provision by administrative (non-clinical) colleagues who receive appointment requests from primary care and the development of a ‘gender inclusive’ referral form which extended far beyond my narrower initial vision of a gender restricted referral pathway (i.e, Male and Female in separate forms)

The collaboration required for this project - both in terms of planning and delivering the service change, and positively responding to challenges when they arose - also created opportunities for learning and progress which would not have emerged, had this project been conducted less intermutually. For example, by sharing the project with SSCA and collaborating openly and transparently and collaborating with NICE with a view to achieving NICE Endorsement, the project has delivered a service change which was far richer and more comprehensive than it would have been. Subsequently, a ‘stand-alone’ piece of work has evolved into a multi-faceted Resource Suite (attachment 2) which other organisations can use to adopt/adapt to greatest benefit in their services.

A further challenge related to the outbreak of Coronavirus which palpably impacted clinical services in our region from March 2020. This project began in February 2020 however the clinical impact was to be measured from early April 2020 when new referral documentation was first rolled-out.

At the same time, referral numbers were seen to drop by 70% in the weeks following COVID-19 related changes in patient choices and service delivery across the primary and secondary care sector. This significantly influenced data liberated in the early weeks and months of the intervention, making initial interpretation of findings, and understanding of the risks and benefits of this service intervention, more challenging. To most succinctly and credibly interpret this data in the wake of the coronavirus outbreak we chose to therefore crystallise our focus into three main questions in the first 6 months of data collection with subsequent attention to the full aims and objectives of the project to be addressed at a later stage in data collection.

The three focus questions were:

1). How has the project influenced cancer diagnosis rates?

2). How many patients are referred with breast pain as their only symptom? and

3). How many patients with breast pain as their only symptom receive a subsequent breast cancer diagnosis?

Findings were then compared with those of a 2019 service audit. For the project to be considered a success, cancer diagnosis rates compared with 2019 should not be adversely affected, patients referred with breast pain should be reduced and the number of cancers diagnosed in patients with breast pain as their only symptom should remain below screening rate (approximately 1%) and unchanged compared with 2019.

Table 1)

Phase 1 - Preliminary work

- Close collaboration with clinical commissioning group lead

- Close collaboration with primary care lead and primary care teams

- Internal review of trust advice & guidance process to include specific areas of enquiry relating to: breast pain, nipple pain, eczema pain

- Explanatory letter sent out to all regional referring primary care teams with links and supporting guidance

- In-service collaboration through regular presentations at Trust Clinical Governance meetings with regular Cancer Alliance review

- Redesign of current breast symptom referral form to align with NICE guidance, capacity/demand enhancement and improved patient experience

Phase 2

- Ongoing data collection and dissemination to partners across Surrey and Sussex Cancer Alliance and stakeholders.

Phase 3

- NICE collaboration and consideration for NICE Shared Learning and Endorsement.

Phase 4

- Dissemination to Cancer Alliance partners throughout NHS and NICE Stakeholders to further enhance patient experience, outcomes and service provision in Suspected Cancer Recognition and Referral (NG12) processes.

Key findings

Description of Initial Findings

Phases 1 and 2

Initial findings have been consistently promising with no change in cancer diagnosis rates, a significant reduction in referrals for patients with breast pain as their only symptom and no cancers diagnosed in patients referred with breast pain as their only symptom.

By June 2020, referral rates for patients with high index of suspicion symptoms were approaching those of the same month in 2019. This indicated the impact of COVID-19 was normalising in terms of patients referred with urgent breast symptoms and increased the potential significance of findings and their relationship to the service change rather than coronavirus.

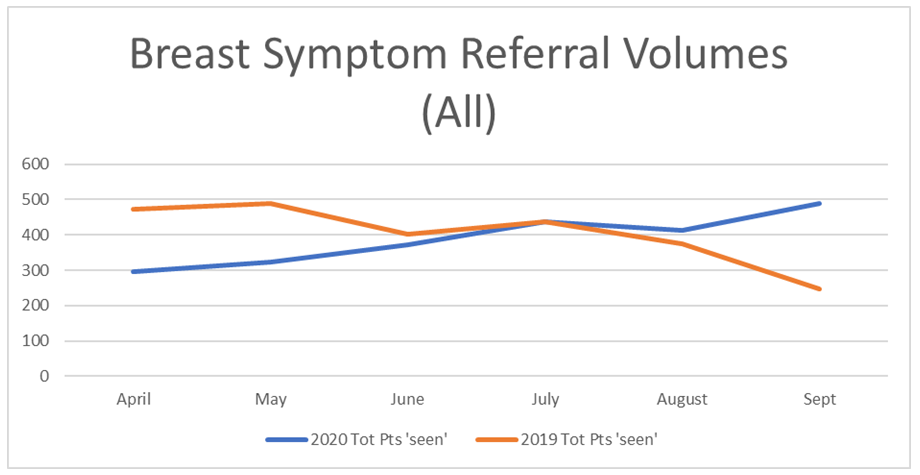

To give context around the performance of our service April-September 2020, compared with the same (pre-COVID) period in 2019, Table 2 below demonstrates referral volumes for 2020 (in blue) were seen to fall considerably for April from 476 in 2019 to 296 in 2020, corresponding with the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. By July of each year, the 2020 and 2019 referral numbers are comparable at 437. However, during August and September 2020 (traditionally quieter times due to the summer holidays), referral rates continued to rise in 2020 and by September of this year, the referral volume almost mirrored our pre-covid ‘peak’ referral volumes seen in May 2019.

Time will tell if this September 2020 elevation reflects a balancing effect following the dearth of referrals in April and May 2020, or if this service change does not in itself act to reduce overall referral volumes.

Table 2

Focus Question 1: How has the project influenced cancer diagnosis rates?

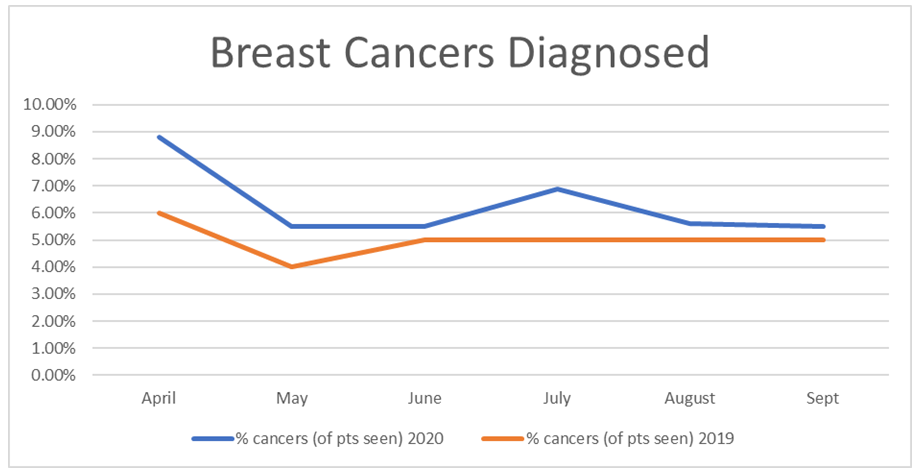

Table 3 demonstrates percentage cancers diagnosed since the service intervention to be consistently higher than 2019 rates, even (albeit by ½%) in September 2020 when we were seen to receive close to double the referral volume of 2019. In April 2020 8.81% of patients referred received a breast cancer diagnosis compared with 6.0% in April 2019. By September 2020, the percentage of cancers diagnosed in 2020 more closely mirrored the outcomes of 2019 with 5.5% of patients receiving a diagnosis of breast cancer in 2020 compared with 5.0% inn 2019. Consequently, it can be concluded that the service change is not adversely impacting urgent cancer referral and subsequent diagnoses.

Table 3

Focus Question 2: How many patients are referred with breast pain as their only symptom?

When considering referrals for patients with breast pain, Table 4 highlights that volumes for the six months post intervention in 2020 have been labile but low. The lowest volume of referrals at 8.7% was in July and the largest at 16.6% in September. It is valuable to also highlight the audit outcome for patients referred with breast pain alone in June 2019 (column in orange) which was prior to the service intervention and which shows a significantly higher referral volume of 28.4%, demonstrating a 42% reduction in low index of suspicion referrals of this type for the first six months of 2020, compared with 2019.

Focus Question 3: How many patients with breast pain as their only symptom receive a subsequent breast cancer diagnosis?

In line with the outcome from our 2019 audit, the findings of this service change demonstrated that none of the patients referred to our service with breast pain as their only symptom, in the six months following the service intervention, were diagnosed with breast cancer.

Phase 3

NICE Endorsement

We submitted the resource suite to NICE for endorsement consideration. NICE were supportive and made recommendations to further align this suite of resources with NICE guidance and quality standards. This included a recommendation that the resource was strengthened by providing clearer signposting relating to patient information provision and preferences (NG12) and the cancer diagnosis ‘triple assessment’ process (QS12). This feedback was welcomed and the resource amended accordingly. Details are now live on the NICE Endorsement homepage and on the ‘tools and resources’ tab of NG12 and QS12.

Phase 4

Details of the resource suite are now available via NICE and have also been disseminated to bodies including the Cancer Alliance (via Surrey & Sussex Cancer Alliance), The National Breast Screening Service, The Association for Breast Surgery and the Health Service Journal. The project is due to be presented at the Association for Breast Surgery Conference (May 2021) and has been submitted to the Patient Safety Congress for consideration in relation to their conference in September 2021.

Additional Outcome:

Gender Inclusive Referral Form Development

We were inspired to develop a new breast symptom referral form following feedback from a project stakeholder who challenged our initial Male/Female specific referral forms and highlighted the importance of gender inclusivity moving forward. Initially, we were not sure how to address this problem and began networking with other colleagues to see if they had any suggestions. We were subsequently introduced to regional LGBTQ+ Network colleagues who were incredibly helpful and supportive and who subsequently enabled us to successfully develop a ‘next generation’ iteration of the original Male/Female forms. These forms are now merged into a single ‘Gender Inclusive’ form which has been added to the Resource Suite for access and adoption by other services.

Key learning points

Secure senior level buy-in at an early stage

The degree challenges impacted upon project progress and its ultimate success depended heavily on the support of key stakeholders, secured in the early part of the project.

Promote co-production and shared power in project delivery

Keeping an open mind throughout collaboration with key stakeholders facilitated improvements that had not been envisioned or considered.

Collaborate widely and openly with key stakeholders

Open and transparent collaboration with stakeholders in all areas created opportunities for learning and progress which would not have emerged, had this project been conducted less intermutually.

Be prepared to adapt to the unpredictable – Covid-19

Remaining cognisant of the impact unpredictable external events may have on the project (in this case Covid-19 impacting referral patterns/service delivery) and adapting data gathering approaches contemporaneously, facilitated optimal understanding of project and its outcomes.

There is always more to learn

We are mindful that a key element missing from our understanding of this project is that of the ‘user’ perspective. To understand this more we are currently developing feedback questionnaires to send to primary care referrers and patients using this new service pathway and plan to use their responses to shape and improve the pathway moving forward.

Embrace challenges and look to collective goals

When passionate about a project and its outcomes, it can sometimes feel threatening to be challenged when you are working so hard to make a difference. We have learned however that embracing challenges really are the most amazing opportunities to create incredible outcomes, and by working with those who are passionate enough to challenge your vision and share their own with you, the opportunities for all to gain are limitless.